|

| Safavid Empire |

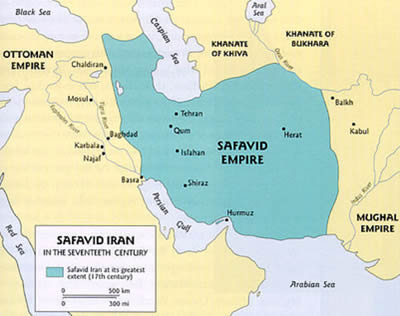

The Safavid Empire was established as the Mongol il-Khan government declined and the Safavids were victorious over the numerous Turkish tribes who had established independent fiefdoms in Persia (present-day northern Iran) during the 13th and 14th centuries.

During this tumultuous period, a number of Sufi, Islamic mystical orders emerged; one order, named after its founder, Shaikh Safi al-Din (1252–1334), created a network of followers who gradually viewed the head of the order as the shah or king. By the 15th century, the Safavid rulers adopted the title padishah or king/emperor.

The Safavid shahs asserted that they were descendants of Ali and the last Twelver Shi’i imam, who was believed to have gone into occultation to reappear at some later time. Religious zealots, the early Safavids attacked Christians as well as those of Turkish ethnicity. They also waged a long and ultimately futile series of wars on the rival Sunni Muslim Ottoman Empire.

|

While the Sunnis asserted that any true Muslim could rule the society, as Shi’i, the Safavids believed that the rulers of Muslim societies should be the descendants of Ali, the prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law, and his sons, in particular the martyr Husayn. These conflicting views over the legitimacy of rule set the two empires on a rival course that would last for over a century.

The first Safavid king, Shah Isma’il reigned from l501 to 1524 and established Twelver Shi’i Islam as the state religion. However he moved away from the Sufi foundations of the empire. Unlike the Ottomans, who generally assimilated new cultural styles and allowed great latitude of languages and practices within their territories, the Safavids enforced the separate identity of Persian culture and language.

In a series of battles with the Ozbegs and the Ottomans, Shah Isma’il consolidated Iran as a unified state. His successor Shah Tahmasp (reigned 1524–76) waged war with the rival Ottoman Empire for control over northern Iran and Iraq as well as attempting to extend Safavid control around the Caspian Sea and into Georgia.

|

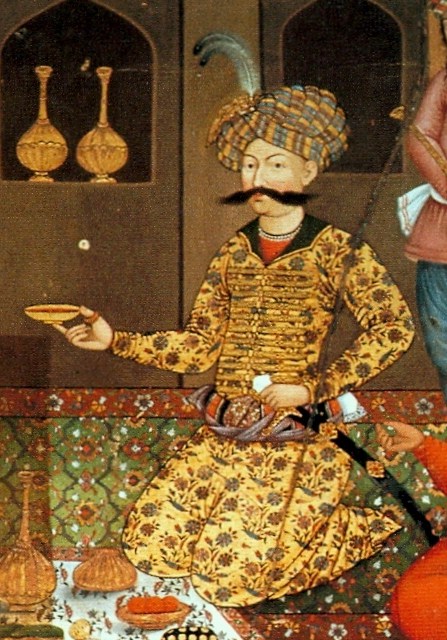

| The first Safavid king, Shah Isma’il reigned from l501 to 1524. |

The Safavid Empire reached its zenith under Shah Abbas the Great of Persia (reigned 1588–1629), who ruled with an iron fist. Abbas managed to destroy the rival Turkish Gazilbash tribes, reform the army, and create a prosperous economy based on the trade of luxury goods, especially silk brocades. Unfortunately he left no able successor and after his death the empire entered a long period of decline.

Safavid society was composed mostly of rural villagers as well as nomadic pastoralists and an urban elite. The Shi’i clergy or mullahs also held considerable power, particularly over the largely illiterate peasantry, who looked to the clergy for religious and political guidance.

|

Many mullahs were large landowners and used the revenues from their property to provide independent financing for religious schools and foundations. Thus when the central authority in Persia was weak, the mullahs often became a political force in their own right.

Safavid rulers were dependent on taxations and revenues from vast Crown or state land and often used land to reward loyal officers and bureaucratic officials. Under Abbas I, the Crown also had a state monopoly over the sale of silk and encouraged a lively trade with western European powers as well as with Russia.

Safavid rulers, like the Ottomans, were keen patrons of the arts and literature. An illustrated Shahnameh, book of kings, with hundreds of intricate miniature paintings was one of the most famous productions of the court artists. The Safavids maintained a lavish court from their capital in Isfahan and enjoyed playing polo and chess.

|

| Shah Abbas the Great of Persia |

Foreign envoys often commented on the sumptuous attire of the Safavid elite and the lavish lifestyle of the court. However every seven years, the used clothes of the royalty were burned and the gold and silver threads saved for reuse in new textiles.

Although the shahs after Abbas I were not as able or dynamic, the empire survived throughout the 17th century largely because it faced no major external threats. In the early 18th century, the Safavids were threatened by several outside forces. In 1722, tribes from neighboring Afghanistan took Isfahan, but a counterattack by Shah Tahmasp II (reigned 1722–32) restored the city to Safavid control for a short period.

Meanwhile, Ottoman forces took advantage of Safavid weakness to extend their authority into northern Persia. Further Afghan attacks effectively destroyed real Safavid power by 1726.

Remnants of the dynasty continued to assert their authority as shahs, but the death, by assassination, of Nadir Shah in 1747 marked the formal demise of the once great Safavid Empire. Toward the end of the 18th century, the new Qajar dynasty emerged as the new shahs over Persia.

|

| A 19th-century drawing of Isfahan |